Pre-exposure prophylaxis access, uptake and usage by young people: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators

Abstract

Background:

Objective:

Design:

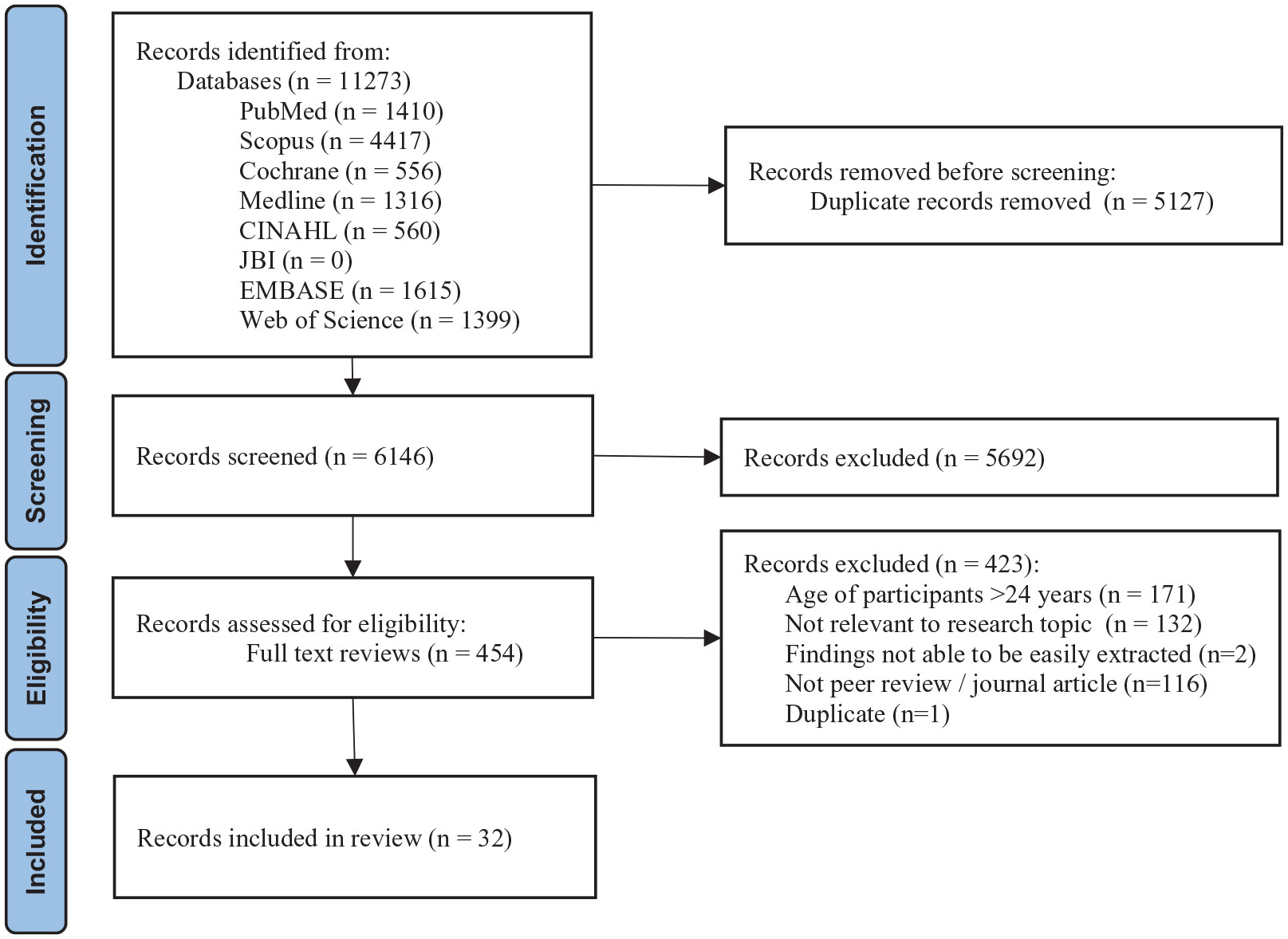

Data Sources and Methods:

Results:

Conclusion:

Registration:

Plain language summary

Introduction

Methods

Review registration

Search strategy

Inclusion criteria and study selection

Data extraction, analysis and quality assessment

Results

| Author (year) | Country | Study design | Study/programme | Aima | Participant details | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative articles | ||||||

| Atujuna et al. (2021) | South Africa | Qualitative interviews | iPrevent | Explore family influence AYAs’ approach towards and use of PrEP | – 18–24 years – Male and femaleb – Self-identify as heterosexual and MSM | – PrEP use was influenced by family support; family attitudes; family disclosure, and other family members using PrEP – Dimensions of family closeness (i.e. close, in-between and loose-knit) were important in contextualizing family influence on PrEP use |

| Baron et al. (2020) | South Africa and Tanzania | Qualitative interviews | EMPOWER | Understand the role and benefits of peer-based clubs incorporating an empowerment curriculum for AGYW taking PrEP | – 16–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – Club participants reported increased self-esteem and self-efficacy, reduced isolation, greater insight and strategies to address gender-based violence – Clubs provided a safe space for sharing problems and provided strategies to improve partner communication |

| Birnholtz et al. (2021) | US | Qualitative interviews | Exploring gay and bisexual MSM’s knowledge and perceptions of PrEP, and the barriers they perceive | – 15–19 years – Male – Self-identified as MSM | – Despite PrEP awareness participants were unsure of insurance coverage and out-of-pocket costs – Participants felt parents and providers would not be knowledgeable or supportive – Participants were reluctant to share their use of PrEP on social media | |

| Camlin et al. (2020) | Kenya and Uganda | Qualitative interviews | SEARCH | Deepen the understanding of PrEP demand and early uptake among young women and men | – 15–24 years – Male and female – Sexual orientation not stated | – HIV severity was perceived as low, uptake was motivated by high perceived HIV risk, and beliefs that PrEP use supported life goals – Men viewed PrEP as helping to safely pursue multiple partners – Women felt they had to ask male partners permission to use PrEP, and saw PrEP as a way to control risks relating to transactional sex and limited agency to negotiate condom use |

| Crooks et al. (2023) | US | Open-ended cross-sectional survey | Explore barriers to PrEP uptake experienced by Black girls and women in Chicago, US | – 13–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – Content analysis identified barriers to PrEP uptake including side effects, financial concerns, medical mistrust, lack of PrEP knowledge and misconceptions, stigma, privacy concerns | |

| Gailloud et al. (2021) | US | Qualitative interviews | Inform the development of adolescent-specific strategies to make PrEP more accessible | – 15–17 years – Male and female – Self-identified as heterosexual or bisexual | – PrEP awareness was low; however, the majority were enthusiastic when informed and felt it empowered them to have control over their health. – Multiple barriers were identified, including confidentiality from parents low perceived need, concerns about adherence and side effects – School-based health centres were considered trusted sources of confidential, accessible care | |

| Hartmann et al. (2021) | Kenya | Intervention design | Tu’Washindi na PrEP | Describe the participatory process used to develop and refine the locally relevant multilevel intervention, | – 15–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – Barriers to PrEP use that were considered for intervention development included; individual (e.g. knowledge, confidence, personal agency); interpersonal (gender roles and intermate partner violence); Service provision (provider judgement/stigma); Community (Poverty, unintended pregnancy, inequitable gender norms, stigma) |

| Hess et al. (2019) | US | Qualitative interviews | ‘‘Good to Go’’ Programme for HIV testing | Investigate reasons for not using PrEP among YMSM accessing to HIV testing services | – 18–24 years – Male – Self-identify as MSM | – Barriers to PrEP included daily bill burden, low perceived risk, side effects, stigma, social or provider influence on decisions, preference for current prevention strategy |

| Marsh and Rothenberger (2019) | US | Case report | Case report of a young black MSM who accessed PrEP however acquired HIV due to cessation of use | – 18 years – Male – Self-identified as MSM | – The young man was able to successfully access PrEP but was unable to adhere to the regimen and engage in follow-up care, ultimately acquiring HIV – Barriers to adherence were difficulty swallowing large tablets | |

| McKetchnie et al. (2023) | US | Qualitative Interviews | Explore barriers and facilitators to PrEP among YMSM and their perspectives on peer navigation to improve uptake/adherence | – 17–24 years – Male – Self-identified as MSM | – Multiple factors influence PrEP uptake/adherence including perceived costs, anticipated stigma, sexual activity, relationship status – establishing pill-taking routines is an important adherence facilitator; and peer navigators could offer benefits for PrEP adherence | |

| Muhumuza et al. (2021) | Uganda, Zimbabwe and South Africa | Qualitative interviews and FGD | CHAPS | Explore barriers and facilitators to uptake of PrEP among adolescents/young people, to inform PrEP implementation | – 13–17 and 18–24 years – Male and female – Sexual orientation not stated | – Barriers included individual factors (fear, side effects); interpersonal (parental influence, sexual relationships); community (peer influence, stigma); institutional (clinic wait times, provider attitudes); structural (cost, modality, accessibility) – Facilitators included individual factors (high risk perception); interpersonal (peer influence, social support); community (adequate PrEP information, efficacy/safety); institutional (convenient/responsive and appropriate services); structural (access/availability, costs) |

| Pintye et al. (2021) | Kenya | Qualitative interviews | PrIYA Programme | Evaluate modifiable factors that impede PrEP use among women receiving PrEP within maternal and child health and family planning clinics | – 15–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – PrEP use/adherence was facilitated by encouragement from close confidants – Pregnancy helped conceal PrEP use due to normalised pill-taking during pregnancy, concealment became more difficult postpartum – Frequently testing HIV-negative reassured AGYW of PrEP efficacy and motivated persistence |

| Rogers et al. (2021) | Kenya | Qualitative interviews | PrIYA Programme | Understand factors influencing PrEP decision-making among AGYW to inform tailored PrEP implementation strategies | – 15–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – Known or suspected partner infidelity motivated use however potential partner reactions was a barrier – Among pregnant AGYW, the responsibility of motherhood staying healthy and remaining HIV-free, was a strong motivator – Fears of negative impacts on fertility or reductions in contraceptive effectiveness led to declining PrEP. – Supportive peers facilitated by PrEP decision-making |

| Santos et al. (2023) | Brazil | Qualitative interviews | PrEP1519 study | Explore the PrEP perceptions and experiences of young GBMSM, considering the intersecting social markers of difference and how they constitute barriers and facilitators | – 16–20 years – Assigned male at birth – Self-identified as MSM | – Willingness to use and adhere to PrEP is part of a learning process, production of meaning, and negotiation in relation to HIV/STIs and the possibilities of pleasure – Accessing and using PrEP makes several adolescents more informed about their vulnerabilities, leading to more informed decision-making |

| Shorrock et al. (2022) | US | Qualitative interviews | PUSH Study | Using an ecological framework examine the lived experiences of PrEP barriers among young Black and Latinx SMM and TW | – 17–24 years – assigned male at birth – MSM and TGW | – Barriers were identified across the individual, family, community and structural level including low perceived HIV risk, fear of disclosure, stigma, barriers relating to insurance/cost and medication use – Partners with HIV encouraged PrEP use |

| Vera et al. (2023) | Kenya | Qualitative interviews | Understand AGYW experiences with pharmacy-based PrEP, reasons for preferring pharmacy-based PrEP delivery | – 15–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – AGYW preferred pharmacies for accessing PrEP and were willing to pay for PrEP even if available for free at healthcare clinics – Reasons for pharmacy preference included accessibility, lack of queues, and medication stockouts, privacy, anonymity, autonomy, and high-quality counselling from study nurses | |

| Zapata et al. (2021) | US | Cross-sectional online FGD | Explore the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV prevention among young sexual minority men | – 17–24 years – Male (including transgender men) – Self-identify as MSM | – Negative effects of COVID-19 pandemic causing limited and disrupted access to HIV testing, PrEP, and post-exposure prophylaxis, and lack of appropriate services – PrEP barriers were compounded by COVID-19-related challenges including relocating back home with family needing to concealing identity/PrEP use; fears COVID-19 by attending clinical appointments | |

| Quantitative articles | ||||||

| Bonett et al. (2021) | US | Randomised controlled trial | PUSH | Explore how economic vulnerability, sexual network-related factors, and individual HIV risk are associated with the PrEP continuum | – 15–24 years old – Male – Self-identified as MSM | – High willingness/intention to use, yet 82% not currently taking PrEP. – Health insurance (aOR = 2.95, 95% CI = 1.60–5.49), having ⩾1 PrEP users in sexual network (aOR = 4.19, 95% CI = 2.61–6.79), and higher HIV risk scores (aOR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.34–1.97) were associated with being further along the PrEP continuum |

| Hong et al. (2021) | US | Cross-sectional survey | Examine how COVID-19 and associated public health measures affected sexual behaviour and PrEP use among YSMM | – 17–24 years – Male (including transgender men) – Self-identified as MSM | – 15% of PrEP users discontinued use during COVID-19 and reported decreased sexual activity – 20% reported difficulty getting prescriptions/medications from doctors or pharmacies – Among those who met CDC PrEP criteria 86.5% were not using PrEP | |

| Macapagal et al. (2020) | US | Cross sectional survey | Describe PrEP awareness, use, and perceived barriers among adolescent MSM | – 15–17 years – Male – Self-identified as MSM or same sex attracted | – Awareness of PrEP (54.8% of participants) was associated with older age, having used GSN applications, and greater HIV knowledge – Being unsure how to access PrEP (56.1% of participants) was associated with more partners, lower HIV knowledge, and never having talked to a provider about PrEP – Believing that one could not afford PrEP was predicted by greater perceived risk of HIV | |

| Moskowitz et al. (2021) | US (incl. Puerto Rico) | Cross-sectional survey | SMART | Our study aims to explore where adolescent MSM fall on the Motivational PrEP Cascade | – 13–18 years – Assigned male at birth. – Self-identified as MSM | – 53.9% were identified as eligible PrEP candidates. Of those identified as appropriate only 16.3% of candidates reached preparation (stage 3; seeing PrEP as accessible and planning to initiate PrEP) and 3.1% reached PrEP action (stage 4; prescribed PrEP) – Factors associated with reaching later stages were being older, being out to parents, and engaging in previous HIV/STI testing |

| Sila et al. (2020) | Kenya | Cross-sectional survey (quant) | PrIYA Programme | Evaluate psychosocial characteristics, behavioural risk factors for HIV, and PrEP awareness and uptake among AGYW seeking family planning services | – 15–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – 89% of AGYW were aware of PrEP; 76% had at least one PrEP eligibility criterion as per national guidelines; only 4% initiated PrEP – PrEP initiators more frequently had high HIV risk perception than non-initiators (85% vs 10%, p <0.001) – Low perceived HIV risk (76%) and pill burden (51%) were common reasons for declining PrEP |

| Tapsoba et al. (2021) | Kenya | Cohort study | DREAMS | PrEP persistence among AGYW who initiated PrEP as part of the DREAMS programme | – 15–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – PrEP programme persistence varied by county (p < 0.001), age at PrEP initiation (p = 0.002), marital status (p = 0.008), transactional sex (p = 0.002), GBV experience (p = 0.009) and current school attendance (p = 0.001) |

| Tapsoba et al. (2022) | Kenya | Prospective study | DREAMS | Extent of programme persistence and the level of protection from HIV infection among programme attendees | – 18–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – Among AGYW perception of being at moderate-to-high risk for HIV if not taking PrEP was associated with persistence (aOR, 10.17 [95% CI 5.14 to 20.13], p < 0.001) – >90% who continued PrEP indicated they were using PrEP to prevent HIV, although almost all had non-protective TFV-DP levels |

| Whitfield et al. (2020) | US | Cross-sectional survey | Understand the prevalence of and factors associated with PrEP use among a large sample of young and adult sexual minority men | – 13–24 years – Male – Self-identify as MSM | – Older age was positively associated with both former and current PrEP use – YSMM who identified as gay (vs bisexual), lived in the Northeast, Midwest, and West (vs South), had their own health insurance (vs those on their parent’s), had recently been diagnosed with an STI, and had recently used a drug all had higher odds of being a current PrEP user | |

| Zeballos et al. (2022) | Brazil | Cohort study | PrEP1519 study | Describe PrEP discontinuation among MSM and TGW and to investigate the associated factors for PrEP discontinuation | – 15–19 years – Self identify as MSM or TGW | – Multivariate analysis demonstrated that TGW (aHR = 1.63; 95% CI: 1.02–1.64) and adolescents with a medium (aHR 1.29; 95% CI: 1.02–1.64) or low (aHR 1.65; 95% CI: 1.29–2.12) perceived risk of HIV infection had an increased risk of discontinuation, whereas the adolescents with a partner living with HIV had a lower risk of discontinuation (aHR 0.57; 95% CI: 0.35–0.91) |

| Multi-methods articles | ||||||

| Barnabee et al. (2022) | Namibia | Mixed-methods | DREAMS | Explore whether and how PrEP service delivery through community and hybrid community-clinic models results in improved PrEP persistence among AGYW | – 15–24 years – Female – Sexual orientation not stated | – In the community and hybrid models, PrEP persistence was related to: – Individualised service delivery offered refill convenience/simplicity – Consistent interactions and shared experiences fostered social connectedness with providers and peers. PrEP/HIV-related stigma was widely experienced outside of these networks – Referral to unfamiliar PrEP services and providers for PrEP refill triggered apprehension and discouraging use |

| Horvath et al. (2019) | US | Multi-methods | Project Moxie | Describe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness, willingness to use PrEP, barriers to facilitators of PrEP uptake, and PrEP | – 15–24 years – transgender and gender nonbinary (TGNB) – 75% self-identified as LGBQ | – Despite PrEP awareness most perceived low HIV risk resulting in low PrEP interest – Barriers to PrEP utilisation included cost, previous negative experiences of medical institutions, medical mistrust, concerns about disclosure, concerns about hormone interaction and insurance coverage |

| Moskowitz et al. (2020) | US | Mixed-methods | SMART | Better understand the role of parents in adolescents’ attitudes towards PrEP | – 13–18 years – Assigned male at birth – Self-identified as MSM | – Most perceived parents would be unsupportive of PrEP and would likely be angry, accusatory, and punitive if PrEP use was discovered – Accessing PrEP independent of parents was thought to increase health autonomy, agency, and prevent awkward conversations about sex. – Low self-efficacy to communicate with parents about PrEP contributed to participants feeling PrEP was not ‘right’ for them, resulting in lower PrEP interest |

| Owens et al. (2021) | US (incl. Puerto Rico) | Mixed-methods | SMART | Understand factors that either facilitate or hinder engaging in PrEP follow-ups and understand ASMM’s beliefs about PrEP follow-up appointments | – 13–18 years – Assigned male at birth – Self-identified as MSM | – 73.0% had heard about PrEP, 45.3% were unsure if PrEP was right for them and 50.4% were unsure if they intended to take PrEP. – Older age was associated with greater confidence in being able to attend follow-up appointments – Barriers included fear of ‘outing’ oneself to parents, concealing appointments, costs, insurance, reliance on parental transport |

| Wood et al. (2019) | US | Mixed-methods | To discover barriers and facilitators of PrEP adherence in young transgender women and MSM of colour | – 15–24 years – Assigned male at birth – MSM and TGW | – Adherence barriers included stigma, health systems inaccessibility, side effects, competing stressors, and low HIV risk perception. – Facilitators included social support, health system accessibility, reminders/routines, high HIV risk perception, and personal agency. | |

| Wood et al. (2020) | US | Mixed-methods | PrEP Together | To characterise perceived social support for young men and transgender women who have sex with men taking PrEP | – 15–24 years – Assigned male at birth – MSM and TGW | – Participants characterised support as instrumental (e.g. transportation); emotional (e.g. affection); and social interaction (e.g. taking medication together) – Key characteristics of PrEP support figures included closeness, dependability, and homophily (alikeness) with respect to sexual orientation |

| Theme/sub-theme | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge, perceptions and experiences influence PrEP use | ||

| Is PrEP for us and is it worth the hassle? – knowledge perceptions, and experiences of young people influence PrEP use | ||

| • Lack of awareness of PrEP and uncertainty of efficacy • Concerns of reduced efficacy of hormonal contraceptives and affecting pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding • Lack of representation of young people in advertisements and endorsements • Concerns and experiences of side effects • Aversion to and difficulties taking pills • Inconvenience of follow up appointments, tests and daily pill taking | • User experience and testing negative at follow up appointments improved normalisation of use, awareness of use • Incorporating PrEP into current routine, for example,with other medications helped adherence • A treatment buddy, someone to take pills with or partner who is on antiretroviral therapy (ARV) for HIV treatment helped with adherence | |

| Not ‘risky’ enough to take PrEP – perceptions of HIV risk impacts PrEP uptake | ||

| • Not considering themselves to be at enough risk • PrEP associated with being ‘promiscuous’, having multiple sexual partners or engaging in ‘risky’ sexual practices • Not feeling scared of HIV and expressed greater fears of other issues such as accidental pregnancy, or cancers | • Higher perception of risk, combined with higher levels of HIV knowledge and engagement with STI/HIV services • Partners having sex outside the primary relationship increased the perceived risk of HIV, prompting PrEP use for their personal protection | |

| Gatekeepers versus cheerleaders – the impact of interpersonal relationships on PrEP use | ||

| The ‘freedom’ to use PrEP – Family attitudes led to concealment or support for PrEP use | ||

| • Parental and family concerns about PrEP efficacy and side effects • Parental concerns and perceptions of young people having sex under the age of 18 or before marriage • Misperceptions that PrEP was used to ‘sleep around’, is an illegal substance, or used for HIV treatment • Fears of parental repercussions/punishment for sexual identity and behaviours, having to ‘out’ themselves to parents to access PrEP • Prevented from using PrEP (e.g. discouraging use, confiscating, throwing pills out) | • Being able to discretely take PrEP, for example, transferring the pills into another bottle • Family members supporting appointment attendance, list a family member as clinic contact, and have family provide pill reminders. • Support from parents of sexual orientation/behaviours enabled comfort in discussing PrEP and encouraged other family members to seek PrEP • Parental support helped young women in African regions conceal PrEP from unsupportive partners | |

| Do I need my partners permission to use PrEP? | ||

| • Accusations of infidelity, scepticism/misperceptions about partner’s HIV status • Traditional power imbalances or normative gender roles and partners engaging in practices such as concurrent sexual partners, polygamy and transactional sex • Partners controlling condom use, experiences of physical violence and reports of partners hiding, confiscating or discarding PrEP pills | • Future plans (finishing school or having a family) • Remain healthy and alive to look after their current children or prevent vertical transmission during pregnancy • Taking PrEP with a partner to protect each other • Privacy/discretion when taking PrEP, for example, transferring PrEP medication into another bottle or convincing partners its medication for pregnancy | |

| Communities can discourage use – community stigma can be overcome by supportive peers | ||

| • Community attitudes and peer disapproval/judgement • Fearful of people thinking ‘you have the disease [HIV]’ • Fears of judgement and rumours regarding pill recognition, being seen attending clinics, or judgement of sexual behaviour that PrEP is being taken to ‘sleep around’, being labelled a ‘whore’ or ‘dirty’ | • Social clubs/groups and peer support provided connection and shared experiences, motivation and support for PrEP uptake and continuation • Social/peer support helped participants hide PrEP use from unsupportive partners • A treatment buddy provided encouragement and adherence reminders • Community use and positive attitudes aided in normalising, encouraging and empowering young people to use PrEP and attending clinics • Rejection of stigma enabling personal agency and autonomy | |

| The healthcare system paradox – the healthcare system itself limits healthcare access | ||

| • Access difficulties including lack of proximity to healthcare providers/pharmacies offering PrEP and a need to rely on parents transportation to access these clinics, clinic closures, long clinic wait times, health centres running out of medications • Lack of gender and sexuality affirming healthcare providers • 3-monthly follow-up appointments were inconvenient, unmanageable, and resulted in scheduling conflicts (e.g. school, extracurricular activities, unanticipated events) • Confidentiality concerns about providers disclosing PrEP use to parents • Cost of PrEP restricts consistent access (e.g. medications, travel, healthcare appointments, unexpected financial strain due to unstable employment/ living costs, and inability to afford PrEP without parental health insurance) | • Proximity to affordable local clinics, school-based clinics and affirming care • School/college-based health clinics that assured confidentiality, and no parental involvement • Providing PrEP at no cost and at local clinics/pharmacies | |

| HCP practices and attitudes influence care – Negative experiences led to medical mistrust | ||

| • Negative experiences with healthcare providers, including judgement or discrimination of participants ‘lifestyle’, sexual orientation, or number of sexual partners • Lack of HCP knowledge, lack of supportive and affirming care • HCP not providing PrEP to bisexual men | • PrEP adherence counsellors and regular reminders helped young people maintain adherence. • Trust in HPC • Being offered practical advice on side effect management, discontinuation, missed dosages and re-initiation | |

Knowledge, perceptions and experiences influence PrEP use

Is PrEP for us and is it worth the hassle? – Knowledge perceptions, and experiences of young people influence PrEP use

. . . .I think it requires campaigns to be done in the population like you moving around encouraging young people to take PrEP and you people telling us why it’s good. (female 21 years; Zimbabwe)44

Even if you just bring tablets and put them there, I just vomit. Some may fear to take PrEP tablets and say that “I rather fall sick with the thing [HIV] than taking those tablets.” (female 13–17 years; Uganda)44

Not ‘risky’ enough to take PrEP – Perceptions of HIV risk impacts PrEP uptake

Some youth now days do not see HIV/AIDS as a serious disease, just because they know there is ARVs [antiretrovirals]. Some youths say, “even if I contract HIV I will go to [the] health center and start taking ARVs.”. . .For girls, they are mostly scared about pregnancy and the boys are only scared of being imprisoned for having impregnated a girl. (male; 15-24 years; Uganda)37

Gatekeepers versus cheerleaders – The impact of interpersonal relationships on PrEP use

The ‘freedom’ to use PrEP – Family attitudes led to concealment or support for PrEP use

You’re afraid to even ask your parents, it’s like basically saying, ‘Oh, I want to have gay sex’. And so it’s something that I try and find a way to discreetly do without my parents knowing if possible. And if it’s not possible, it’s probably something I’d just not do. (assigned male at birth; 15 years; U.S.)36

I actually shared [my PrEP use] with my mum. . . .I had a lot of quarrels with my husband and I had to run back to my mum’s house . . . So my mum sat me down and told me that there is no need to keep running away all the time. That I should stay put because it is men’s nature to wander away [have outside partners] when they have cash. She advised me that I should look for a way to protect myself [against HIV] (female; 20 years; Kenya)45

Do I need my partners permission to use PrEP?

On my side, when I tell my partner that I use PrEP and he does not agree, I will use it secretly. Because these drugs are in bottles and to them, they feel they are ARVs. And because of that, he keeps beating me all the time and because of that I am forced to use them secretly in hiding. (female; 23 years; Kenya)40

My husband is also taking his medicine [ARVs] at the same time with me, so I have not seen any difficulty [in remembering to take PrEP]. Sometimes if I forget, he reminds me. Sometimes my phone alarm might go off and he reminds that it is time [to take PrEP]. (female; 24 years; Kenya)45

Communities can discourage use – Community stigma can be overcome by supportive peers

And when I say that I take PrEP, she [a friend] thinks that I have sex with everyone under the sun, and that’s why I take PrEP. There’s much prejudice to a person who takes PrEP (male; 17 years; Brazil).47

The best way for them [peers] to use it is when they see me using it. . .Yaahh, they want protection, they need to see me having used it and am alive. Then they will say let’s go boys and we get them [PrEP pills] together (male; 19-21 years; Zimbabwe).44

I feel like you should just be happy that I’m trying to prevent getting HIV instead of worrying about what I’m doing. I feel like as long as I’m taking care of my health, there shouldn’t be a problem. (female; 16 years; United States)39

The healthcare system paradox – The healthcare system itself limits healthcare access

I live in a conservative rural community and have to drive a long way to a supportive care facility, I just choose to not take PrEP at all right now because of the frequent required visits. (male; 17-24 years; United States)51

If you know that you are not sick you will say let me go do something else with that money and you overlook your health. . . .if not for paying [for PrEP] then it will be very easy for me. (female 17 years; Uganda).44

HCP practices and attitudes influence care – Negative experiences led to medical mistrust

There was one time that it wasn’t my primary care doctor. It was a different doctor. . . . and she spoke heavily religiously and was telling me, because she thought I had depression, she was saying going to church would help that. And I felt in my mind if she believes this as a doctor and is recommending this to me, I probably should not tell her about being gay (assigned male at birth; 17 years; United States).36

Discussion

| 1. Include young people as stakeholders in the development and design of interventions and messaging to ensure promotion is acceptable, culturally tailored, sustainable and accessible 2. Provide targeted and universal health promotion messaging to reach boarder populations of young people 3. Expanding adherence support through the use of mobile apps or clinic text message reminders 4. Including PrEP as part of positive sexual health plans and risk-reduction packages targeted towards young people 5. Reframe HIV prevention and PrEP as a positive and proactive sexual health choice to reduce stigma 6. Co-designing HIV prevention strategies with young people in collaboration with their broader intergenerational community networks to facilitate culturally congruent uptake and use of PrEP and enhance related health literacy 7. Develop accessible peer and social support to provide safe spaces for young people to feel engaged, validated, provide adherence support and empowerment to navigate difficulties in maintaining PrEP use 8. The provision of PrEP at no or subsidised costs for young people and ensure young people are aware of initiatives to provide financial assistance and access to PrEP 9. Education and support for healthcare providers to improve information, education and provision of PrEP to young people 10. Expand PrEP delivery through non-traditional models of care (e.g. through nurse-led and pharmacy-led PrEP, or flexible PrEP refill schedules) to improve accessibility, anonymity and autonomy |

Strengths and limitations

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

ORCID iD

Footnotes

References

Supplementary Material

Please find the following supplemental material available below.

For Open Access articles published under a Creative Commons License, all supplemental material carries the same license as the article it is associated with.

For non-Open Access articles published, all supplemental material carries a non-exclusive license, and permission requests for re-use of supplemental material or any part of supplemental material shall be sent directly to the copyright owner as specified in the copyright notice associated with the article.

Cite

Cite

Cite

Download to reference manager

If you have citation software installed, you can download citation data to the citation manager of your choice

Information, rights and permissions

Information

Published In

Keywords

Authors

Metrics and citations

Metrics

Journals metrics

This article was published in Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease.

View All Journal MetricsPublication usage*

Total views and downloads: 1339

*Publication usage tracking started in December 2016

Altmetric

See the impact this article is making through the number of times it’s been read, and the Altmetric Score.

Learn more about the Altmetric Scores

Publications citing this one

Receive email alerts when this publication is cited

Web of Science: 4 view articles Opens in new tab

Crossref: 4

- Factors Associated With Interest in HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Men and Women in Kisumu County, Kenya: A Secondary Analysis of the RV393 Cohort Study

- Motivations for Starting and Stopping PrEP: Experiences of Adolescent Girls and Young Women in the HPTN 082 Trial

- “Taking Charge and Being Responsible”: A Qualitative Study of Meaning Making and Motivations for Preexposure Prophylaxis Adherence Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Sexual Minoritized Men Engaged in Alcohol Misuse in Kentucky

- HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis re-initiation among men who have sex with men: a multi-center cohort study in China

Figures and tables

Figures & Media

Tables

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBAccess options

If you have access to journal content via a personal subscription, university, library, employer or society, select from the options below:

loading institutional access options

Alternatively, view purchase options below:

Access journal content via a DeepDyve subscription or find out more about this option.